In the Museum the shells are presented in entomological cases and each shell is accompanied by a drawing to show its features better as it is often rather small.

This small size of most local shells is evident at first sight: nothing like the large sea shells or colourful tropical land shells. In our shells the prevalent colours are shades of brown, acting as camouflage in forest litter, or the light colours of rock snails that reflect the sun’s rays.

The danger of dehydration is ever present for these small invertebrates; to this the snail’s response is to be active during the damper times of the day, such as after a shower, or to thicken its shell as in the case of the Pomatias elegans (show case no. 709) and seal it with a horny operculum.

The operculum and separate sexes is a peculiarity of the primitive Prosobranch Gastropods which include both land and water forms.

For example, among the former there are the curious Cholostoma (C. septemspirale, C. henricae, C. philippianum; case no. 709) with a cone-shaped shell, found in rocky ares, many isolated by glacial activity, including several species and sub-species; and we must not forget the minute Acicule (case no. 709), living on land and having a smooth or finely ribbed shell and frilled edge round the mouth of this shell.

A conspicuous member of the water Prosobranch is the Viviparus ater (case no. 724) which lives in watery areas by Lake Santa Croce, but also in a pond near Tambre, and, as the name indicates, it gives birth to live offspring.

The rare and delicate Paladilhiopsis virei (case no. 724) on the other hand, lives in a world unknown to us: in underground water, feeding on encrusted but not green microorganisms.

The most primitive family of the Polmonate Gastropods is the Ellobidi (Archaeopolmonates) with the minuscule Carichium (C. marie and C. tridentatum, case no. 709) to be seen in rotting leaves in beech woods, and the mysterious Zospeum (Z. spelaeum), blind inhabitants of the caves under the local Prealps.

The Polmonates include 2 orders: the Basommatofori, with their eyes at the base of the tentacles which are reduced to 2 and the Stilommatofori whose eyes are on the top of the higher pair of tentacles.

The first group includes species living in the fresh water of canals, streams ponds and lakes.

Unlike the fresh water Prosobranchs the Basommatofori Polmonates arrived in these waters via land and not via the sea.

This is why the pretty pond limnea (Limnaea stagnalis, case no. 723) has lungs as opposed to gills and has to come to the surface to breathe in oxygen from the air.

This also applies to the smaller forms like the Radix auricularia, the R. peregra or the Galba truncatula (case no. 723): the latter 2 species may be seen in slow moving streams and springs.

While the limnae have dextral whorls the fise have sinistral whorls with the aperture of the shell on the left: all 3 Italian species can be found in the wetlands of Lake Santa Croce and Paludi. These include the rare Aplexa hypnorum, today more and more threatened by man-made changes to the landscape, but still plentiful in this area.

Another family is the Planorbidae, the largest of which, the planorba maggiore (Planorbarius corneus, case no. 723) lives near Lake Santa Croce, the only site known in the Province.

This species was once called “fresh water crimson”: to make the most of the oxygen in the water, their blood, like ours, contains haemoglobin pigment and, if disturbed, they emit small red drops in the hope of disorientating a possible predator.

The shell of this group to be found in Alpago with other species like the Planorbis and Gyraulus (case no. 723) is easily recognisable by its disc shape.

Land living species include nume-rous minute members which live in grassland tufts, woodland litter and rock rubble: their splendid shells are striking for their elegant or bizarre shapes.

To appreciate them properly you need a stereoscopic microscope with 20 – 30 enlargement, and in this case you can perceive the delicate ribbing on the Pagodulina and Sphyaradium (case no. 710) and on the Vallonia costata and Gittenbergia sororcula (case no. 711), the small spines on the strange Acanthinula aculeata (case no. 711), the mouth armour of the menacing Odontocyclas kokeilii (case no. 710) or the keg shaped Vertigo (case no. 710).

The pygmies of the group are the truncatelline (case no. 710) and the Punctum pygmaeum (case no. 712), whose name is a good indication.

The condrine are a typical rock-living species which feed on the lichen covering calcareous rocks: the Chondrina avenacea (case no. 711) includes 2 natives of the upper-middle Piave valley. (C. a. latilabris and C. a. veneta).

The Polmonati Stilommatofori includes the rather strange clausilie group (case no. 717-718): their shell is small, a long, narrow torpedo shape.

The opening usually has numerous plica which help us to recognise the species and it is sealed with a small calcarean plate called a clausilio.

The species living in rocks and trees are different; they hide in small cracks in the bark or rock: Macrogastra Cochlodina and Charpentieria (case no: 717) are the most common.

In the collection is also the rare Neostyriaca corynodes (case no. 718) which lives on the Vette Feltrine (mountains near Feltre), the second site known in Italy, and the Fusulus interruptus (case no. 718), an eastern Alps species found in the Cansiglio forest.

The zonitidi (case no. 713) include carnivorous species like the Aegopinella and the Oxychilus and forms able to enter caves like the troglophile Aegopis gemonensis.

A similar but larger species is the Aegopis verticillus which lives in the Cansiglio beech woods, the western limit of its territory.

Other members of its family are the small vitree whose Vitrea minellii is native ti the Cansiglio plateau and Carnian Alps.

The vitrine (case no. 712, table 716) include other carnivores in which the animal is covered by a thin hood which is too small to contain it completely (Eucobresia, Vitrina, Vitrinobrachium and Carphatica). Some of these can be seen in winter moving across the snow.

The slugs, without an external shell, but usually having the remaining vestiges of one inside their mantle have been illustrated with some drawings. One of the most common is the great black slug Limax bielzi and the grey slug (L. Maximum) which are found mainly in damp beech woods; the Arion lusitanicus however is the red slug which has become notorious for the damage it does in vegetable gardens.

This slug was introduced by accident in Puos d’Alpago at the end of the 60s and in a few years had spread throughout the area of Belluno.

Many species of the Hygromiidi family (case no. 718), as the name suggests, prefer damp habitats, in particular woodland litter.

The shells of the Trichia, Petasina, Helicodonta and Ciliella are brown and often covered with tiny bristles, while the Hygromia cinctella is easily recognisable by its carenated shell.

One of the Helicidi is the campylee (case no. 719), found on rocks and walls with a nearly flat, spiral shaped shell.

The Chilostoma illyricum is locally known as the “s’ciosela del diaol” for its blackish body and has an unpleasant flavour if eaten.

The other species of this group (C. cingulatum and C. ambrosi) are peculiar to the arid rocks of the eastern Alps.

An entomological show case is dedicated to the Cepaea nemoralis (case no. 720), often seen in park and garden hedges; the variations in colour and patterns on the shell, with dark bands on a background of yellow, pink or white, are quite striking.

The most common form is the “pentafasciata” (5 bands), but the bands may be less, merging, or even missing. All these exhibits belong to the same species, even if there is considerable phenotype variety.

The Arianta arbustorum (together with the Arianta stenzii) also belongs to the Helicidi family; it is locally called the “s’ciosela de montagna”, living in Alpine pastures above 1,500 metres, and is collected as a gastronomic delicacy particularly around Chies d’Alpago and Lamosano where an event, “Sagra de le s’ciosele”, is based on it. Its collection has now been regulated by local authorities1.

The “s’cios” (Helix pomatia) is represented in the collection by 3 snails weighing over 100 grammes each and being over 10 years old; this is certainly the largest and best known snail in the local fauna.

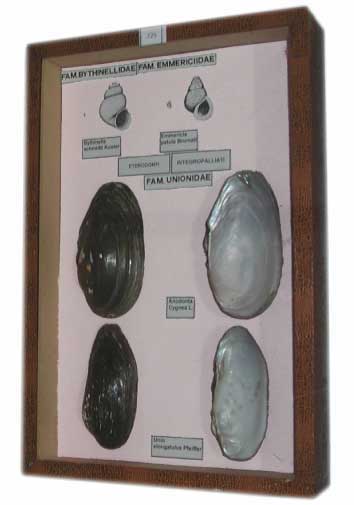

Returning to the water, this time we consider the bivalves, molluscs with their shell made up of 2 valves joined by a hinge, such as the great Anodonte and Unio (case no. 725) which are still to be found in the muddy floor of the lakes of Santa Croce and Vedana.

They dig down with their foot, feeding on particles filtered from the water which passes through their gills; they are great filtrators with an important role in water depuration.

Their shells can be found on the northern shores of Lake Santa Croce, often broken by seagulls’ bills or by some crow living in the area.

The pisìdi (Pisidium, case no. 726) are much smaller bivalves to be found in almost any pool of fresh water: the mud and their size protect them from sight.

With a little curiosity and care you can find for yourselves many of the species displayed in the collection: a walk through the woods, through a village or even in your garden would be sufficient. Good hunting!